Tendinopathy Rehab: It’s About Slow-Heavy Loading, Short Bouts, Real Results (a blog post based on the work of Dr.Keith Baar, PhD and tendon expert from University of California-Davis)

[Disclaimer: this is a blog post for education purposes only and should not be viewed medical advice as each case could be uniquely different from the next. None of this material is truly original and is inspired by the work of Dr.Baar]

Tendons aren’t tiny ropes you “stretch out.” They’re living, load-sensing tissues that connect compliant muscle to stiff bone. That job is tricky: too stiff and you risk muscle strains; too slack and you lose spring and control. Smart rehab respects that physics and the underlying biology.

Below is a plain-English blueprint—rooted in molecular-to-athlete evidence—for getting cranky tendons to settle down and get strong.

Tendon vs. ligament (and why it matters)

-

- Ligaments tie bone to bone (stiff → stiff). For them, stiffer is better: higher stiffness = higher failure strength.

-

- Tendons tie muscle to bone (compliant → stiff). They’re regionally tuned: near the muscle they’re more stretchy; near the bone they’re stiff. Good rehab preserves that gradient.

What actually makes a tendon strong?

-

- Collagen amount (think “how much material is there”)

-

- Collagen cross-links (think “molecular rebar”)

-

- Your body builds enzymatic cross-links (via lysyl oxidase) with loading.

-

- Non-enzymatic sugar cross-links accumulate with aging and high blood glucose—one reason tendon problems are more common in diabetes.

-

- Collagen cross-links (think “molecular rebar”)

Speed of loading changes the tissue (viscoelasticity 101)

Tendons behave a bit like water:

-

- Slow loading → collagen fibers can slide past each other → you break some cross-links → the muscle-end of the tendon becomes less stiff → better for tendon health and pain.

-

- Fast loading (plyos, sprints) → collagen acts like a sheet → you add cross-links without breaking old ones → tendon gets stiffer → great for performance, but if overused too soon, injury risk climbs.

The rehab core: slow-heavy loading (not just “eccentrics”)

Why slow-heavy? Because slow creates the shear that remodels the muscle-end of the tendon; heavy gives a real signal to rebuild collagen.

Effective options:

-

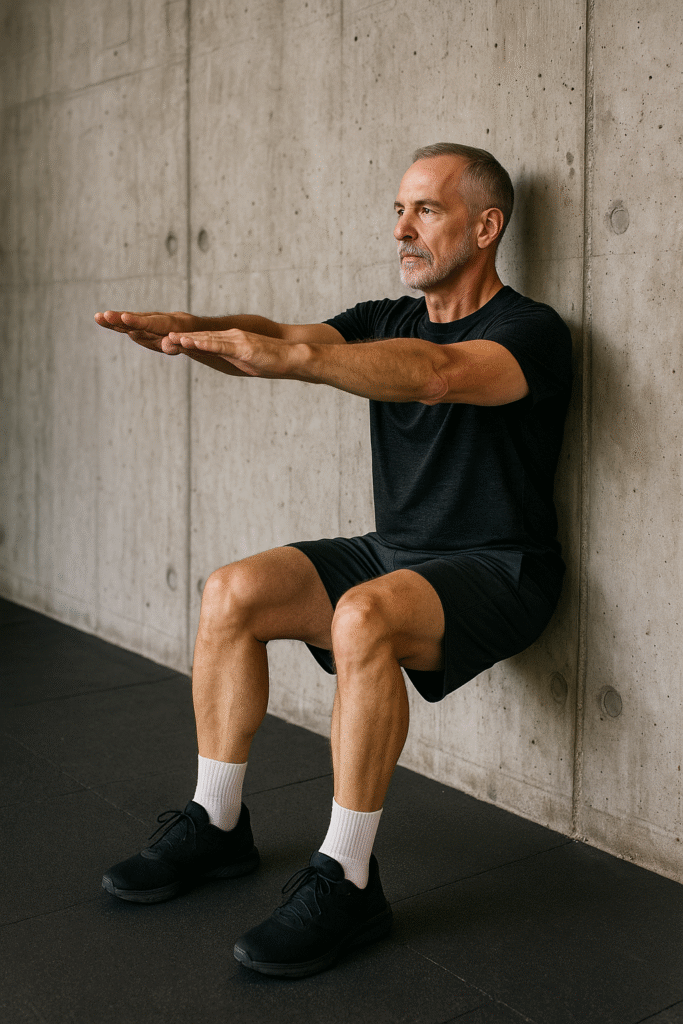

- Slow isometrics (the slowest contraction of all): heavy holds, pain-calming dose

-

- Slow eccentrics (slow phase working with gravity/load)

-

- Slow concentrics (slow phase working against gravity/greater load)

All three work because they’re slow. Eccentric isn’t magic—tempo is.

- Slow concentrics (slow phase working against gravity/greater load)

“Micro-dosed” bouts beat marathons

Tendon and bone cells respond maximally within ~5–10 minutes—then go refractory for ~6 hours. Translation:

5–10 minutes of quality loading, then ~6 hours off, repeated, outperforms continuous training for tendon remodeling.

Sample weekly rhythm (principle, not a prescription):

-

- 4–7 days/week of 5–10 min slow-heavy tendon work (e.g., heavy calf raises, slow leg press, slow split squats, heavy isometric holds), separated by ~6 hours.

-

- When pain is calm and capacity rises, layer in fast work (hops/plyos) to recapture performance—after the tendon tolerates slow-heavy well.

Stress-relaxation holds for stubborn tendinopathy

With chronic tendon pain, injured regions often get “stress-shielded”—load flows around the weak spot. Heavy isometric holds at fixed joint angles (e.g., leg press ~90°/90° for patellar tendon) use viscoelastic stress-relaxation to “soak” load into the under-loaded tissue so it can realign and rebuild collagen. This is particularly useful in central-core patellar tendinopathy.

Muscle’s matrix matters too

Strength isn’t only muscle fiber size. The extracellular matrix (ECM) inside muscle transmits force laterally between fibers before it even reaches the tendon. Loading turns on signaling (e.g., ERK → EGR1) that ramps fibrillar collagen production in muscle ECM—another reason heavy, well-dosed work boosts usable strength without chasing hypertrophy for its own sake.

Practical guardrails

-

- Don’t chase only “performance stiffness.” If you pile on sprints/plyos before restoring the muscle-end compliance with slow-heavy work, you raise the odds of muscle strains and flare-ups.

-

- Progress load, keep it slow. Use tempos you can feel (e.g., 3–5 seconds each way or sustained heavy holds). Pain during work should be tolerable and should settle within 24 hours; if it spikes, reduce intensity/volume.

-

- Be consistent, not heroic. Short sessions done often (with 6-hour spacing) beat occasional grinders.

-

- Metabolic health amplifies results. Better glucose control = fewer problematic sugar cross-links.

Example tendinopathy session (template, not medical advice)

-

- Isometric primer (2–5 × 30–45s heavy holds at relevant angle; 2–3 min rest)

-

- Slow-heavy sets (3–4 sets of 6–8 reps, 3–5s down, slight pause, 2–3s up)

-

- Stop at ~5–10 minutes of actual tendon loading, then walk away. Come back ~6 hours later or the next day.

When symptoms are quiet and capacity is up, layer fast work: small hops → larger hops → multidirectional plyos → sprint/change-of-direction work.

FAQs

Is eccentric loading required?

No. The key is slow. Eccentric, slow concentric, and heavy isometrics all create the shear that remodels tendon where it needs it most.

How often should I train a painful tendon?

Think short bouts (5–10 minutes of true tendon work), repeated with generous spacing (≈ 6 hours). Consistency beats marathon sessions.

Why did rest or a boot make me feel “springy”… then I tweaked something?

Inactivity increases tendon stiffness near the muscle end. You may feel bouncy at first, but without rebuilding the compliance there, the muscle takes the stretch and strains.

Do fast hops and sprints help or hurt?

They’re essential later for performance. Early on, they add cross-links (stiffness) without fixing the pain driver. Build capacity with slow-heavy first.

I have diabetes—is that relevant?

Yes. Higher blood glucose increases sugar cross-links, making tendons less forgiving. Load still helps, but managing glucose improves tissue quality over time.

What about nutrition?

Some protocols pair gelatin/collagen an hour before loading to bathe tissues in the needed amino acids during the stimulus. It’s an adjunct to, not a substitute for, the right loading.

Examples of Global Dosing Defaults (apply to all rows unless noted)

-

- Isometrics (analgesic / entry): 4–5 × 30–45 s @ ~70–85% effort, 2–3 min rest

-

- Slow isotonic (capacity): 3–4 × 6–8 reps, 3–5 s down, brief pause, 2–3 s up

-

- Bout length: 5–10 min actual tendon loading → stop → ≥6 hr before next bout

-

- Progression gate: symptoms calm, next-day baseline, quality reps preserved

Tendinopathy loading example table

| Region | Key pain provokers (to monitor) | Primary isometric positions (entry) | Slow isotonic “meat & potatoes” | Stress-relaxation / special notes | Plyometric / return-to-spring build |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patellar (jumper’s knee) | Decline squats, stairs, jumping/landing, prolonged sitting | Leg press or hack squat ~90° hip / 90° knee, heavy hold; Spanish squat holds (strap behind knees) | Heels-elevated back squat (tempo), leg press (3–5 s ecc), split squat (front-leg bias), decline (25°) squat if tolerated | Heavy 90/90 holds create stress-relaxation to “soak” load into central tendon; keep tibial angle consistent. Start pain-calming bouts 2×/day before sport | In-place pogo → bilateral line hops → unilateral line hops → depth drops (20–30 cm) → approach jumps. Progress only after 2–3 weeks of stable symptoms |

| Achilles (mid-portion focus) | First-step pain a.m., uphill, tempo runs, jumps | Seated calf raise hold (knee ~90°), standing calf raise hold (knee extended) at mid-range | Seated and standing calf raises heavy, full ROM, 3–5 s ecc; progress to straight-knee and bent-knee single-leg; load via machine or Smith | Prioritize mid-range heavy holds early; use a step edge later only if symptoms are quiet. For central thickening, emphasize isometrics + slow eccentrics | Ankle pogo → bilateral → unilateral hops → skipping/ankling → sub-max bounds. Add contact-time targets only after pain is stable |

| Proximal Hamstring (high hamstring “a pain in the butt”) | Sitting on hard surfaces, hill sprints, deep hip flexion hinges | Isometric bridge holds (double → single-leg), isometric hip hinge hold with torso ~30–45° forward, slight knee flexion | Romanian deadlift (hip-dominant, neutral spine), hip thrusts (progress to single-leg), slider eccentrics (hamstring curl), 45° back extension slow | Avoid end-range hip flexion early. Use hinge-angle-controlled holds to load tendon without compressive irritation. Build tolerance to sitting with graded durations | Low-amplitude line hops (sagittal) → A-skips → wicket runs / dribbles → gradual re-intro of hills. Sprinting last; add fast eccentric late |

| Lateral Elbow (ECRB) | Gripping, lifting with elbow ext/pronation, mouse use | Wrist extension isometric (elbow ~20–30° flex, forearm pronated or neutral) against band/dumbbell; grip holds (dynamometer or towel) | Slow wrist extension (dumbbell over edge of bench), pronation/supination slow, radial deviation loading; later add compound pulls with neutral handles | Keep shoulder relaxed; scapular engagement reduces local overload. Use isometric grip ladders for work-task bridging. Short, frequent bouts beat long sets | Med-ball taps (light) → rebounder catches (neutral grip) → low-amplitude drop-catch wrist work → sport-specific grips once daily tasks are symptom-free |

Flare control, progression, and red flags (quick reference)

| Topic | Do this |

|---|---|

| Flare response | Next-day pain > baseline or >3/10 during → cut load 20–40% or shorten bout; switch to isometrics only for 48–72 h; keep easy cardio |

| Weekly structure | Prefer many short bouts over marathons: e.g., AM isometrics + PM slow isotonic for 5–10 min each; leave ≥6 hr between tendon bouts |

| Load ramp | Increase only one variable at a time (load or volume or complexity). Hold gains for 7–10 days before the next bump |

| When to add plyos | Pain ≤2/10 during/after, no 24-h backlash, slow-heavy loads feel crisp, and daily triggers (stairs, first steps, gripping) are quiet |

| Adjuncts | Footwear/orthoses (Achilles/patellar), workplace grip/handle swaps (lateral elbow), seat pad/hip hinge depth control (prox hamstring) |

| Red flags (refer out) | Sudden “pop,” visible defect, inability to load calf/quad/hamstrings or extend wrist, night pain unlinked to load, progressive neuro deficits |

Example micro-cycle (plug-and-play, 15–20 min total per day)

| Day | AM (analgesic / primer) | PM (capacity) |

|---|---|---|

| Mon | 4 × 30–45 s isometric (region-specific) | 3 × 6–8 slow isotonic (key exercise above) |

| Tue | 4 × 30–45 s isometric | 3 × 6–8 slow isotonic (second pattern) |

| Wed | Isometric only or light aerobic | Off (tendon rest) |

| Thu | 4 × 30–45 s isometric | 3 × 6–8 slow isotonic |

| Fri | 4 × 30–45 s isometric | Begin low-amplitude plyo if criteria met |

| Sat | Off or easy isometrics | Sport-specific drills if quiet next day |

| Sun | Off | Off |

Bottom line

Tendinopathy rehab is engineering + biology: use slow-heavy loading in short, separated bouts to remodel the tendon’s muscle-end, then re-introduce fast work to regain spring. Respect the tissue’s time constants and it will reward you with durability and performance.

If you want, I can tailor this into specific progressions for patellar, Achilles, or lateral elbow presentations and format it for your client handouts.